Still Falling, Jennifer Grotz’s fourth collection of poems, illuminates the connection between art and time.

One summer several years ago, Jennifer Grotz was in Italy, heading to Rome, when she received word that her dear friend and fellow poet Paul Otremba had been diagnosed with esophageal cancer. Once in the city, she made her way to the Santa Maria del Popolo basilica to view a painting of significance to them both: Caravaggio’s The Conversion of St. Paul.

Completed in 1601, the roughly seven-by-six-foot oil-on-canvas painting depicts the biblical scene in which Saul of Tarsus—en route to Damascus, tasked with seeking out and arresting the followers of Jesus—is suddenly stricken down and blinded by a bright light. He then hears the voice of Christ ask, “Saul, Saul, why do you persecute me?” The experience prompts Saul’s conversion to Christianity.

The drama of this life-altering moment for the man who would come to be known as Paul the Apostle is conveyed through Caravaggio’s use of chiaroscuro, a technique in the visual arts that employs strong contrasts between light and dark within a composition.

Contemplating the scene in front of her, Grotz called to mind Otremba, who had written “Surfing for Caravaggio’s Conversion of Paul” about the painting. Otremba’s work had been composed in response to his teacher, the American poet Stanley Plumly, who’d written his own poem, “Comment on Thom Gunn’s ‘In Santa Maria del Popolo’ Concerning Caravaggio’s The Conversion of St. Paul.” Plumly, in turn, was in dialogue with a contemporary of his, the English poet Thom Gunn, musing on the very same work of art.

“I was talking in my head to Paul and thinking about the conversations that we—all these poets—were having,” she says. “It became a useful way not only to process his illness, but also to use the figurative to think about the literal, and vice versa.”

Chiaroscuro through language

Grotz, who is a professor of English at the University of Rochester as well as an award-winning poet and translator, would eventually distill her meditations into a poem titled “The Conversion of Paul.”

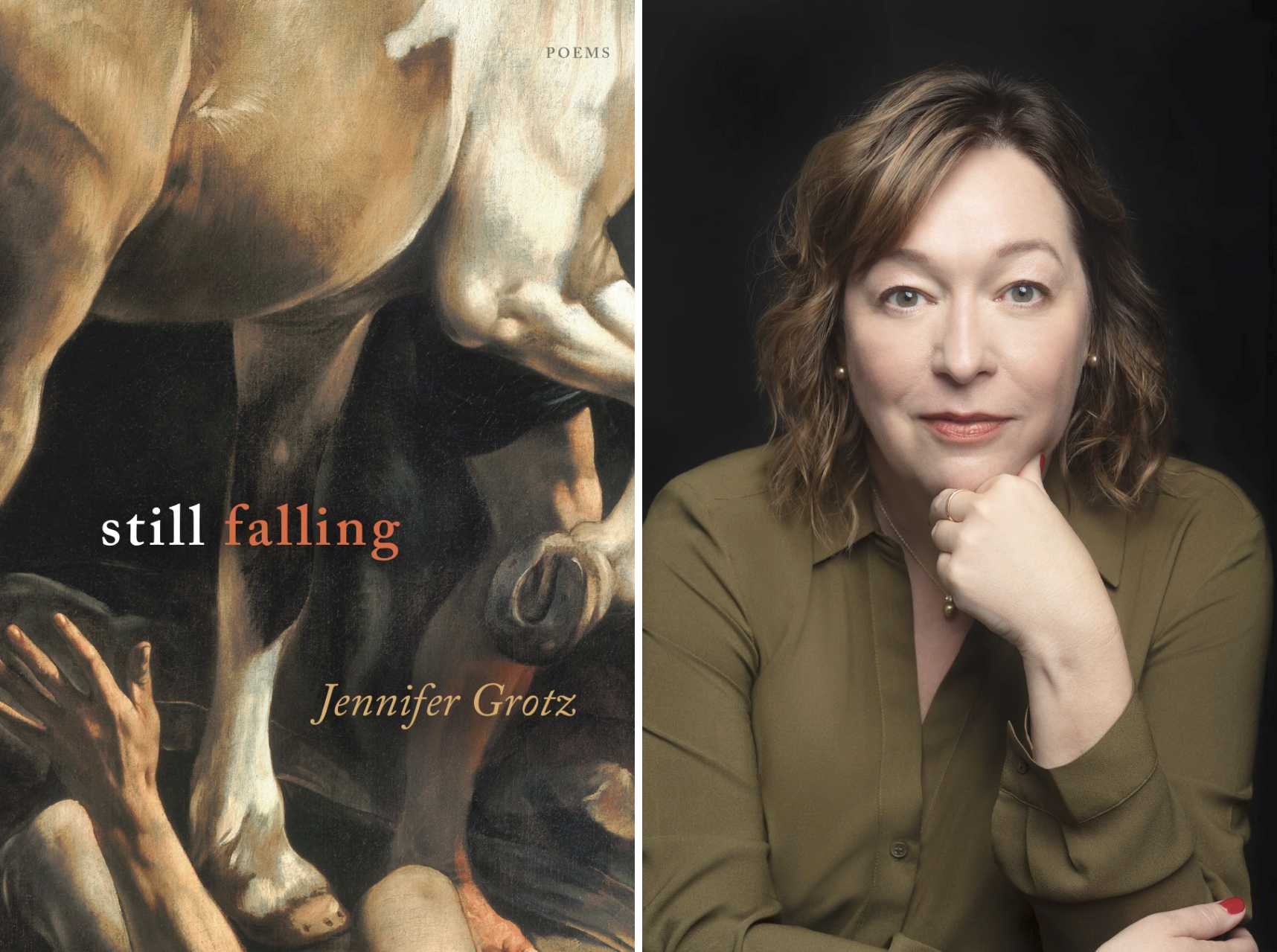

The 79-line poem, dedicated to Otremba, is one of the more than three dozen entries comprising her fourth and latest collection of lyric poetry, Still Falling (Graywolf Press, 2023). The poem is also the one from which the book draws its title as well as the inspiration for the cover art, which features a crop of Caravaggio’s painting.

LISTEN: Jennifer Grotz reads “The Conversion of Paul” from Still Falling, her latest collection of poetry. Grotz made the recording at the request of her friend and fellow poet Paul Otremba before his death in 2019. Jump to the transcript of the poem.

Grotz considers herself an ekphrastic poetic. “I have at least one ekphrastic poem in every book I write,” she says. “It’s an ongoing practice.” Ekphrastic poetry, she explains, is poetry that responds to another work of art, usually in another medium.

The term comes from the Greek word for “description,” but successful ekphrastics goes beyond simply describing another work of art. “It has to think about it, quarrel with it, or use it to leap to something outside the frame or in the world.” (She cultivates this practice in her students, whom she dispatches to the University’s Memorial Art Gallery to contemplate and then write about a holding from the museum’s extensive collections.)

“The Conversion of Paul,” which is available to read on her website, is the main ekphrastic poem in Still Falling. In it, she vividly describes aspects of Caravaggio’s painting, including the sexual overtones (“the red cloak, crumpled like bed sheets” beneath Saul, “arms and legs / as if ready to be taken by God himself”), while toggling between lightness and darkness, both literal and figurative. According to Grotz, “The question becomes, what can only my medium of language do? Can I, for example, make chiaroscuro in language? If so, how?”

More urgently, though, Grotz uses her poem to engage in an ongoing dialogue with Otremba as well as with generations of artists and creators who’ve come before her—some identified directly, others implied:

A lot could be made of how Gunn, then Stan, then you

made a poem out of a painting, but Caravaggio

did it first, making the painting out of verses

from the Bible. All art traffics in some kind of translation.

Which might be another word for conversion.

“As a poet, I’m really interested in voice,” Grotz says, particularly as a means of connecting with the past and present. “Many of the poems in Still Falling were written during the pandemic, when I was alone in my house. I’ve never been more grateful for poetry as a means of conversation, a way to connect with other voices, including those of people I couldn’t talk to anymore.”

A seasoned poet contemplates time and place

Still Falling encapsulates the author’s poetic inquiry into the themes of loss, light, and legacy. The word “still,” suggesting both stagnation and continuity, is juxtaposed with “falling,” evoking a sense of perpetual motion and descent, shaded with the autumnal.

Grotz foregrounds her contemplations of time explicitly with the poems named for months, which appear in the collection in chronological order (“November,” “December,” “January,” “March,” “May,” and “August”). More implicitly, the seasons of life figure prominently throughout the book, which was spurred by a series of losses—including her father in 2015—around the time of the publication of her last book, Window Left Open.

“And then the pandemic came, and everyone seemed to enter this period of grief,” she says.

Grotz’s poetic journey is informed not only by time, but also by her surroundings. She spends nine months of the year living, writing, and teaching in the city of Rochester. References to local landmarks like the frozen Genesee River and the University’s River Campus during wintertime appear in her work, grounding them in the physical world.

Her summers are often spent in sunnier climes, such as Italy and France, where her writing takes on a different hue. “So, when you put them together in a book, it makes a sharp contrast,” she says.

The legacy of poetry

As a senior faculty member at Rochester and the director of the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conferences at Middlebury College in Vermont, Grotz is a custodian of the rich tradition of poetry at both institutions.

Bread Loaf, which was founded in 1926, is one of the country’s oldest writers’ conferences, with literary luminaries including Robert Frost, Louise Glück, and Philip Levine (among others) associated with the program. “It’s a distinctly American phenomenon, this movement of writers coming together to support, mentor, and train each other,” says Grotz.

Rochester also has a notable roster of poets affiliated with the University, be it as students, alumni, faculty, or guests. They include Hyam Plutzik, one of the first poet-professors in the country; Anthony Hecht, who was named the United States Poet Laurate after being on the Rochester faculty for more than two decades; Galway Kinnell ’49 (MA), whose 1982 book, Selected Poems, won the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award; James Longenbach, a faculty member, poet-critic, and Guggenheim Fellow whose work garnered recognition from the American Academy of Poets and Letters; and Ilya Kaminsky, a deaf Ukrainian-American poet and a one-time undergraduate at Rochester.

Longenbach was among Grotz’s mentors. They first met at Bread Loaf in 1995, when he was delivering a lecture on the poetry of Jorie Graham, and she worked with him regularly after joining Rochester’s faculty in 2009. “There was no better person to correspond with about poems,” she said about Longenbach after he died of cancer in 2022.

Now Grotz carries the mantle of being the senior poet at Rochester. “I realize what a precious opportunity and experience it is to talk about poetry and poems with younger poets, to share what I know and to learn from them,” she says. “I count it as a privilege to continue that tradition at Rochester.”

The Conversion of Paul

—for Paul Otremba

Bewildered—something in me is made wild

from looking at it—but something

also chastened, subdued, because

it holds my gaze a long time. It is itself

a unit of time—one bewildering instant

caught by Caravaggio’s imagination—Saul

thrown off his horse, landing on his back,

taken aback, Saul becoming Paul, struck blind,

being spoken to by the light. It seems

none of us really cares for Gunn’s

take on the painting, defiant insistence

of being hardly enlightened, but I admire

the chiaroscuro-like contrast he makes

between Paul’s wide open arms

and the close-fisted prayers

of the old women he notices in the pews

when he turns away. But even if

Paul on the ground is still falling, both

are gestures of blind faith, as Stan calls

it. You call it a bar brawl, all this one-upmanship,

but in your poem you don’t take sides,

you give your own perspective, twenty-first century,

postmodern, belated. You ask what happens if

a hundred people hold the painting in their minds

at the same time. Will it gain a collective dullness,

a tarry film like too much smoke? But I like to think

it would sharpen the focus, deepen the saturation

of the red cloak, crumpled like bed sheets, beneath him.

A lot could be made of how Gunn, then Stan, then you

make a poem out of a painting, but Caravaggio

did it first, making the painting out of verses

from the Bible. All art traffics in some kind of translation.

Which might be another word for conversion. God says

Saul, Saul, why persecutest thou me? It is hard for thee

to kick against the pricks. Which makes me think

of the horse, who should be more visibly

shaken probably from such a flash of light.

No one seems to register how claustrophobic

it all is, difficult to believe it’s happening

outside, where there should be space

for all this stretching out, and the horse

wouldn’t have to raise one hoof so as not

to step on Paul. And the groomsman,

why isn’t he doing anything but

staring down? Like all Caravaggios,

it’s sexual, the arms and legs splayed as if

ready to be taken by God himself,

but it’s really an outsize gesture of shock.

I heard the news of your being sick, Paul,

when I was in Italy. If God himself

is the radiance that struck Saul into Paul,

then what is the darkness swimming around

everything? It makes one feel inside of something,

confined by such dark. Afterwards, the Bible says,

Paul was three days without sight, and

neither did eat nor drink. Now after chemo

you consume a thousand calorie shake

called The Hulk to keep from losing weight.

I went to see the painting when I was in Rome

in September. It is a pleasure to look at a painting

over time. To consider it along with others,

including you, my friend, over decades.

Something in the painting is insistently

itself, intractable, and yet inexhaustible meaning

keeps also being revealed. Paul, thinking of you

when I look at the painting changes it. I see you

vulnerable, surrendered, beautiful and young,

registering that something in you has changed

and what happens next happens to you alone.

And inside you. Conversion is a form of being saved,

like chemo is a form of cure, but it looks to me

like punishment, a singling out, ominous,

and experienced in the dark. When

I used to see the painting, I was an anonymous

bystander. Now I am helpless. It is

and you are, in the original sense, awful.

I can’t get inside the painting

like I suddenly and desperately want to,

to hold him, to help you get back up.

And now, for Paul, everything has changed.

The post A poet’s meditation on loss, light, and legacy appeared first on News Center.